Effort = Effort

The Broken Backlog Creation Nowadays

Here's something I've seen in every single industry I've worked in: planning departments (or portfolio) that don't talk to the people who actually build the product. And if they do talk, they don't actually listen. They have their own agenda.

Managers create quarterly plans. Executives approve roadmaps. Stakeholders sign off or promise timelines for delivery. And somewhere, three floors down or two time zones away, a developer team looks at the plan and thinks:

"Who came up with this? Have they ever seen our current work in progress? This is not possible!"

This isn't a tech problem. It's not an agile problem. It's a century-old management problem dressed up in Jira tickets and Sprint Reviews.

And it's where everything I believe about planning changed.

The "How Long Will It Take?" Trap

If you've ever been in a room where someone asks a development team "how much time do you need for this?", you know what happens next. The room gets quiet. Someone says "it depends." Someone else throws out a number that sounds reasonable but has no basis in reality. And the manager writes it down as a commitment. Even worse: the same question asked on another day, with another half of the team, would produce a completely different answer.

That's not planning. That's politics with a deadline. How many times has anyone actually delivered quality on a timeline that was set with zero understanding of the real effort involved?

Complex products, the ones that matter today, the ones that touch multiple systems, teams, and architectures, don't fit into a spreadsheet cell. You can't estimate your way out of complexity. And yet, every organization I've walked into tries exactly that: squeeze an uncertain, interconnected, multi-team effort into a neat quarterly plan. Then act surprised when it falls apart by week three. Or doesn't deliver three years down the road.

The answers you get aren't based on data. They're based on gut feeling, on what people think management wants to hear, on who shouts loudest in the planning meeting. And that leads to, let's be honest, dumb decisions. Not because the people are dumb. The people are usually brilliant! What's broken is the system they're operating in.

Year Three Of Five.

I learned this the hard way.

Back then I was coaching a team responsible for a core functional operating system. A product so central that if it failed, it would take the whole company down with it. They were in year three of a five-year development cycle, and they were running blind. And out of time.

The people on this team were incredibly skilled. Engineers who understood their domain and previous product inside out. But "nobody" was listening to them. Instead, decisions came from above: plans made in rooms they weren't invited to, priorities set by people who hadn't looked at the code in years. Or even knew what the code meant to the product.

They had Scrum. On paper, everything looked agile. They had Daily Stand-ups, Sprint Reviews, Retros. All the ceremonies, all the artifacts. But the backlog was a catastrophe. The Sprints were a mess. It was structured for a simple product (Epics and Stories in Jira), not for a complex, multi-layered operating system with dependencies reaching into every corner of the organization, as well as external providers. Multiple of them.

The dependencies were immense. The politics were big. The silos were bigger.

And the pressure? If this product wasn't ready by year six, almost 6,000 jobs would be on the line. Entire production chains were dependent on this working.

That's not a hypothetical. That was the actual situation. Real people. Real consequences.

The Scrum Exorcism

Something had to change. Not incrementally. Fundamentally.

So I did what I now lovingly call: a Scrum Exorcism.

I didn't throw Scrum out because Scrum is bad. It isn't. The Scrum implementation had genuinely improved things compared to what came before. But Scrum alone wasn't built for this level of complexity. When your product backlog serves an enterprise-grade operating system and you're treating it like a to-do list for a startup app, you've outgrown the tool. Scaled frameworks like LeSS or SAFe were rejected; the politics didn't allow them to be implemented. Once your system refuses to let the team work on a single Sprint Goal "because of Reasons", then the necessary requirement to do Scrum is out the window.

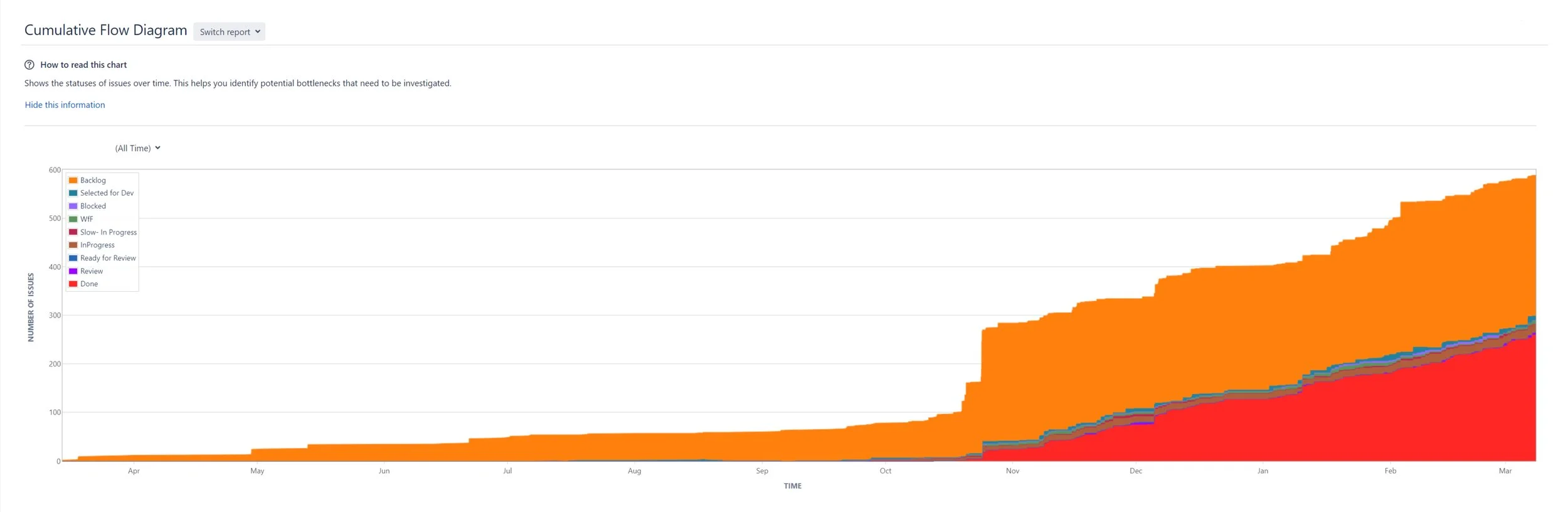

The first thing I did was introduce Kanban. Not as a replacement, but as a foundation. We needed three things desperately:

measurability, transparency, and self-organization.

The team took a leap of faith with me, because time was running out. I barely had more than a month working with them by this point.

We needed to see where work actually was, not where people said it was. We needed to understand how long things actually took, not how long someone wished they would take. And we needed the people closest to the work to make decisions about the work, instead of waiting for permission from three levels up.

The Product Owner and the Department Head were drowning. One person, trying to manage a backlog that was way too big, way too tangled, and way too political for any single human to handle and another person trying to align priorities, incremental dependencies and stakeholder expectations. So we distributed the responsibility: to the people who actually understood the work, while being aligned with the department’s needs.

Can you guess where we started having Initiative Owners?

When Developers Became Initiative Owners

This is where it got real.

Developers. The same people who had been ignored in planning meetings, whose expertise had been overlooked for years. They became Initiative Owners.

Their job wasn't to manage sprints or write user stories. Their job was to look at the big picture: identify the rough scope and effort of an Initiative. Not just for their own team, but across entire departments. Because here's the thing that everyone knows but nobody acts on:

Effort is effort. No matter where it sits, who it belongs to, or when it has to be done.

If your initiative needs backend work, frontend work, infrastructure changes, a third-party integration, or even just writing an email to a different department: that's the effort. All of it. You don't get to pretend the backend team's work doesn't count because "that's their problem." If backend and frontend don't work together, you don't have a product. Period.

This sounds obvious. It is obvious. And yet, almost every organization I've worked with plays the same game: "We're only responsible for X." As if dependencies disappear when you refuse to look at them.

The Initiative Owners changed that. They broke through the silos. Not with political power, but with visibility. Not with blaming the others, but with inviting them for open conversation. When you map out the actual effort across all teams and systems, suddenly the prioritization conversations change. Instead of "what does my management want, and by when?" it becomes "what do WE actually need to do, no matter the department or team?"

6 days average per ticket, all roughly the same size. And when one took 5 weeks? More than half of that time was spent blocked or waiting for feedback. Not a work problem. A system problem. For the first time, this team could answer 'when will it be done?' with data, not a gut feeling.

The Principle Behind It All

This experience is where I solidified a thought I'd been carrying for years. I'd noticed the pattern much earlier in my career, but I was too inexperienced to trust my own thinking. Too junior to say out loud what I could see: that the entire planning paradigm was upside down.

But under the pressure of 6,000 jobs and a product that just had to work, there was no room for doubt. And the principle that emerged became one of the cornerstones of what would eventually become the LIFE Framework (Lean Initiative For Enterprise).

Effort = effort. No matter where, who it belongs to, or when it has to be done. It means: stop pretending that effort in another team doesn't count. Stop planning as if your product lives in isolation. Stop asking developers "how long?" and start asking "what's the full picture? What happens before and after?"

When you take this seriously, when you actually map all the effort, across all the teams, across all the dependencies... you can finally make decisions based on reality instead of politics.

The team that was running blind in year three? They started seeing. Not because someone gave them a better plan from above, but because the people who understood the work were finally trusted to own it.

What This Means For Your Crew

If you're reading this and thinking "that sounds exactly like us", let me tell you: you're not alone. I've seen this pattern in automotive, in software, in financial services, in manufacturing, in HR. The industry changes. The dysfunction doesn't. And I'm not a technical person at all! Every company was pure quantum physics for me. But the system issue never changed.

The question isn't whether your organization has this problem. It almost certainly does. The question is whether the people who understand the work are the ones making decisions about it, or whether they're still waiting for a quarterly plan from someone who's never opened the codebase.

If you want to explore what it would look like to turn your planning upside down, or rather, right side up: get in touch!